#DDMss, 'Digging Deeper 1: Making Manuscripts', recently ended its six-week run with a very good level of success, according to Stanford Online's administrators.* We had a completion rate of 25% from around 4500 registered students--a high percentage for online learning. Of those who filled in our survey, we obtained a satisfaction rate of 98% ('Somewhat Satisfied, 15%; Very Satisfied, 47%; Extremely Satisfied 36%'). I'd be happy with those percentages in a campus course of, say, 12, 24, 45, or 68 students; but here, there were 830 respondents, so those figures suggest we've offered something that's been regarded as worthwhile.

|

| Student Evaluations from 'Digging Deeper 1' |

Now, Manuscript Studies is quite a specialised area of study and research, so we were never expecting 40,000 students to register, as sometimes happens in a 'Massive Online Open Course' (MOOC) like 'Computer Programming' or 'Become an Entrepreneur'. As we were preparing 'Digging Deeper' in the two years before it launched, I hoped we get 2,000 participants in the course's first iteration to help justify the time, effort, and money that went into making the films, the surrounding resources, and the platform's design. To get more than double that number is pleasing, and of these, while a surprising proportion was curators, graduate students, and academics, many more were complete novices, or had engaged in very little formal palaeographical or codicological training. 'Digging Deeper' had to try and meet the needs of this diverse community, which necessitated some rapid responses in weeks 1 and 2, as it became clear we'd taken some things too much for granted. These diverse communities resulted in different uses for the course and dramatically variable learning environments. I know of two institutions that used the course alongside an on-campus seminar, to augment what students were learning in class. I know of many other participants who worked on their own in remote locations, accessing our material through dodgy wi-fi connections, but pleased to be part of a broader community that extended across the world, from Aberystwyth (hello, Mum!) to Austin, Lima to Lisbon, St Petersburg to Sydney.

|

| Imago mundi, c. 1190 Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, 66 |

There has been a tremendous amount of critical and apocalyptic commentary about MOOCs and their potential effect on Higher Education (outlined here https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/05/14/faculty-group-continues-anti-mooc-offensive and here http://news.dice.com/2013/12/18/moocs-fail/, for example. Here's where online learning might be heading: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/08/upshot/true-reform-in-higher-education-when-online-degrees-are-seen-as-official.html?_r=0&abt=0002&abg=0), but I believe such modes of learning have genuine pedagogic and academic value.

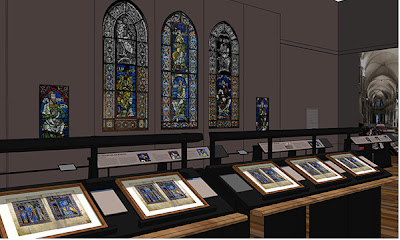

While 'Digging Deeper 1' can hardly claim the 'Massive' status of a MOOC, we put it together to provide something that's not offered on every university campus; to show any interested participants some of the basics about medieval book history, using the resources of Cambridge University Library and Stanford Green Library's Special Collections. We wanted to offer an introduction to the richness and beauty of medieval books and documents, so many of which can now be seen in Open Access repositories. It has been my strong belief for the last decade or so that all of us who look at this material digitally can usefully benefit from a degree of training in what it is that we're seeing and how we might interpret the images we view. Online learning is one way to make Manuscript Studies more widely available, accompanying the increasing numbers of excellent resources to be accessed through the internet. It's also why there is a 'Digging Deeper 2: The Form and Function of Manuscripts' in April 2015, where we'll feature the work of conservators, digital specialists, and non-Western-manuscript scholars (http://online.stanford.edu/). We hope you can join us!

[*The 'Digging Deeper' team is Dr Benjamin Albritton, Dr Orietta Da Rold, Dr Suzanne Paul, and Professor Elaine Treharne with Dr Kenneth Ligda, John Mustain, Jonathan Quick, Andy Saltarelli, Colin Reeves-Fortney, Adam Storek and the EdX Platform team at Stanford.]