In 2010, Christie’s sold a beautiful, de luxe Book of Hours that had been made in Northern France in about 1460. It was listed here: http://m.christies.com/sale/lot/sale/22794/lot/5370918/p/1/?KSID=d57c011f180cba461c0aaa27d5b7d989. The book went under the hammer for £25,000 + auction fees and was sold to a trade buyer. Christie’s description demonstrated the significance of the book. It’s important for all kinds of reasons: its artistic qualities are outstanding, as so many extant Books of Hours demonstrate. Foliate decoration embellished with gold leaf enhanced multiple pages; the regularity of the script suggested an accomplished and experienced scribe. Written into the last opening is a set of unpublished fifteenth-century French prayers. Seventeen full-page illuminations will have provided meditative image-space for users of the book.

Thus, notwithstanding the guesstimated 10,600 surviving Books of Hours, it is a unique and rich witness to private devotional book production at the apogee of the manuscript age. Moreover, in the nineteenth century, when so many antiquarians meddled with manuscripts in ways that varied from vandalistic to fetishistic, this manuscript seems to have been touched up by none other than Caleb William Wing, a famous intervener, who worked for well-known book collectors, such as John Boykett Jarman. Thus, this manuscript, significantly, has quite a bit of its post-facture history and provenance intact, and is a fascinating case study of a book’s life.

And death.

I now own the

‘book’. Or at least, I might be said to own the ‘book’, since I possess the nineteenth-century

binding, the pink silk flyleaves with the book’s distinguished provenance, and

eleven folios of the original medieval core, including the French prayers.

|

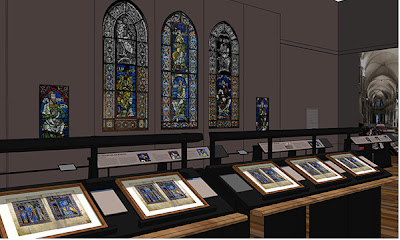

| The remains of manuscript 615 |

But I

do not possess the book and will

never be able to reconstruct it. Why? Because it has, since 2010 (the year two thousand and ten), been broken

up deliberately and sold (mostly via EBay, I think) piecemeal in an act of shocking

and greedy vandalism that I have uncovered in the last two weeks. I should say,

too, that I bought the binding and intact leaves from a trusted American

book-seller, purchased specifically for teaching and assuming the codex had

been fragmented decades ago. He, in turn, had bought the book-shell from a German dealer.

This shattered

shell of a book has proven improbably easy to trace.

It was owned in the

nineteenth century by a well-known collector, Edward Arnold, whose ex libris is still in situ on the front, pink endleaf. Edward Arnold’s very

substantial collection was sold at major auctions in the 1920s and 1930s. In

the Catalogue of Manuscripts Belonging to

Edward Arnold (http://www.archive.org/stream/catalogueoflibra00arnoiala/catalogueoflibra00arnoiala_djvu.txt), this book is his number 615, as recorded

in pencil on the verso of the second flyleaf.

615. B. M. v., cum Calendario, illuminated MS, on vellum, 252 11. [Flemish 15th century], 17 full-page

illuminated miniatures with designed and floriated borders, decorated with angels,

birds, fruit, and grotesque figures, over 250 of the pages having beautiful

painted leafy borders heightened with gold, with many hundreds of illuminated

initial letters, stout small 8vo, modern black morocco extra, with metal

clasps, gauffred gilt edges Saec. XV

I don’t yet know

who bought this book during these auctions, but the book clearly made its way

to Christie’s for their sale in November 2010. Currently, the individual leaves

or individual bifolia are being sold on Ebay by the ‘International Art and Antique

Gallery’, a shop in Leipzig, owned by ‘kunsthandel’ Chidsanucha

Walter e.K (see http://stores.ebay.com/international-art-antique-gallery/Handschriften-Manuscripts-/_i.html?_fsub=3485336017).

This seller has

individual leaves listed on EBay in a variety of languages and with no

meaningful context provided at all. The miniatures are selling for $2,300 or so;

individual leaves for up to $150; bifolia for about $400, depending on the

extent of gold leaf or foliate decoration. I am screen-grabbing every folio as

it appears in an effort to record 'the book'. And in a crisis mode, I bought two bifolia from the Calendar, plus

one leaf with foliate marginal ornamentation, that came up for sale in the week beginning November 11th, so that I can show students how

this book would have looked (would have looked, just three years ago).

I realize that by purchasing these leaves I am directly contributing to the appalling trade in dismembered

books, but these are the only leaves I will buy, despite trying to deal with a feeling

of desperation as I watch this book literally fragment online into irrecoverable bits.

Buying these leaves has also given me the opportunity to comment publicly on

EBay about this particular Leipzig-based seller, so I shall simply be saying that it's a curious thing he has so many leaves from this recently dismembered codex.

I have alerted

Christie’s to the history of this book, since they sold it whole. Christie's (and all the rest of the auction-houses) have, I believe, a major responsibility to sell only to those who demonstrate best practice in antiquarian book-dealing (which wouldn't include mutilation or fragementation). I have also

spoken to colleagues in the antiquarian book trade. There is more that can be

done, I suspect, to stop this myopic and destructive profiteering. I calculate

that the person selling the body parts of this book won’t make much more than

$20,000 in profit. Is biblioclasm of this scale really worth that?