A book like Cambridge, Trinity College, R. 17. 1, unlike the St Cuthbert Gospel, recently acquired for the nation by the British Library (

http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2012/05/the-st-cuthbert-gospel-the-story-of-a-book.html) could hardly claim to be hand-held technology. It is large and unwieldy, weighing at least 20lbs. Also known as the Eadwine Psalter (Google it for lots of images of the eponymous 'prince of scribes' who might have designed the volume) or the Canterbury Psalter, it is one of the most magnificent manuscripts in a century of unparalleled biblio-magnificence. It is half a metre tall and comprises one animal skin per opening and its size means that the reader really has to stand to be able to take in the fullness of the book's folios. If the reader is sitting while examining the volume, most of the upper part of the folio is effectively unreadable. So, the book is not easily used, not easily accessible, and certainly not portable in the way the Cuthbert Gospel is. These manuscripts are the medieval equivalents, in physical terms, of the modern paperback (the little Gospel) and the now non-existent print version of the

Oxford English Dictionary (the large Psalter).

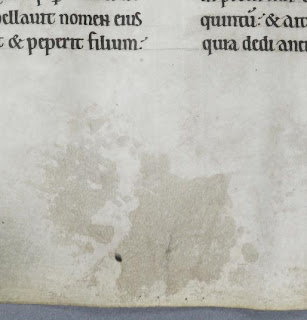

And yet, while looking closely at the Eadwine Psalter a couple of weeks ago, even while noting the absence of browsers' marks or the interventions of engaged readers, it became clear to me that to an extent this volume

was hand-held--time and time again. Moreover, those hands and their literal imprints are very revealingly and entirely haptically presented on every recto of every folio through the cloth-like nature of the membrane in these handled areas, rather than the stiffer composition of the less handled parts of the leaf. What looks like blankness in the expanse of margin at the foot of the folio (well, blank except for the modern foliation) is anything but, then.

|

| Cambridge, Trinity College, R. 17. 1, folio 107r |

And here, of course, the work of art historians like Jennifer Borland and Kathryn Rudy ('Violence on Vellum: Saint Margaret’s Transgressive Body and Its

Audience', in

Representing Medieval Genders and Sexualities in Europe:

Construction, Transformation, and Subversion, 600–1530, eds. Elizabeth

L’Estrange and Alison More [Ashgate, 2011] and 'Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer',

Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, Vol. 2, 1 [2010], respectively) helps us to interpret the evidence for how users interacted with books, often very physically, leaving dirt or erasure behind them through their touching of the book.

But less than dirt or rubbing, I am especially interested in those spaces that appear to be blank, particularly when a folio is viewed as a digital image. Here, it is often the voluminousness, the heft, of a book's materiality that is lost to sight. Within this 'voluminousness', the light and shade, the ebb and flow, the rise and fall of the physical leaf is critical to understanding how the book was received by readers, users, casual passers-through. This is felt most obviously in the fabric of the book and is an integral part of the book's textness, its plenitext.

A second example demonstrates this perfectly and illustrates that even the largest of books can be thought of as hand-held technology. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 2, the substantial Bury Bible, produced in the first half of the twelfth century and now divided into three huge volumes, measures

522mm x 360mm. It was a display volume intended among other things to demonstrate the wealth and authority of the Abbey at Bury St Edmunds. But its de luxe quality did not preclude it from being read; its status might only have added to the moment that a reader had with it, for in this book, every verso of every folio bears the physical testimony of use, even if it's difficult to detect. So intense is the turning of the folio that on some versos, the touch of the successive users' hands has left visible proof of their presence through the abrasion of layers of the membrane:

Blankness here, then, is anything but, and what looks like a stain in the digital image is, in fact, the erasure caused by countless page turnings. Thus, while the manuscript itself may be the antithesis of hand-held technology, to turn the folio is, even so, to hold the hands of readers from centuries past.