In the New York Times on 23rd June (http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/23/opinion/sunday/the-decline-and-fall-of-the-english-major.html?src=ISMR_AP_LO_MST_FB), Verlyn Klinkenborg outlined the so-called 'decline' of the English Major, unhappily conflating the apparent crisis in the Humanities with the falling numbers of students studying English and confusing the issue by lamenting these same English students' alleged inability to write clearly. (What students, by the way, would want to study with a tutor who complained in such a blanket fashion about them?)

There's so much one can say about this article. First, Klinkenborg's experience is not my experience. Some students write beautifully from the outset; others need more time to learn. It was ever thus. It is my job to teach my students the skills they need to be the best that they can be. Secondly, as pointed out here (http://www.theamericanconservative.com/jacobs/the-humanities-again/) and here (http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d11/tables/dt11_289.asp [a reference via Michael Bérubé at https://www.facebook.com/michael.berube.169?fref=ts]), the figures depend on the particular data being manipulated. It was ever thus... again.

But in between the hand-wringing and the prophecies of a Humanities apocalypse, there are two things that strike me as particularly myopic.

1. The first is the common use of the English Literature and Language undergraduate degree as the whipping boy of 'the Humanities'. The 'Humanities'--or, more appropriately, 'Arts'--are much more than just English.

2. The second point is that a good English degree is much more than just 'writing' and 'reading'. A good English degree will train a student in all areas of English Literature. In the study of early literary texts, for example, the skills imparted by reading Old English or Middle English are not only 'clear thinking, clear writing and a lifelong engagement with literature', as Klinkenborg lists, but also patience and meticulousness in the acquisition of translation skills, problem solving at the level of the individual lexeme, team work in class efforts to make sense of tricky syntax, empathy with a literary corpus at first so alien, tolerance of others' beliefs and expression of those beliefs, and so on. Thus, when we talk about an 'English degree', let's remember the field of English is itself varied and broad: it is not a single, uniform set of literary materials; it is not a narrow, individual set of tools. At its best, the field of English is diverse, chronologically capacious, concerned with minutiae as well as big pictures, focused on translation and interpretation as well as reading and writing. As a teacher, I am determined to teach students that what is difficult is worth pursuing; that the hardest work is usually the most rewarding. And as practitioners, we might remind ourselves that this Humanities 'crisis', while hyperbolic now, could actually become self-fulfilling if we continue to talk about our field in the negative ways we've so often seen recently.

Thoughts on the textual and literary, & on text technologies from Babylonian cuneiform to Twitter, with an eye on the medieval

Monday, June 24, 2013

Friday, May 17, 2013

On MOOCs, flip-lectures and the medieval

The Times today reported on a conference about learning techniques that seemed to focus on 'innovation' in the classroom (http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/education/article3767441.ece). Its silly headline reads: '"Medieval" lectures could be replaced by free online courses'. It's a headline that makes no sense, since it implies that 'lectures' (which take many different forms), are 'medieval' in origin (when they've been a tested form of education since the classical period), and will be eliminated by 'courses' (which are not synonymous with 'lectures') that are 'free' (so what?) and 'online' (only available in electronic form? Really?).

No one should believe this.

The report goes on to say that Don Nutbeam, Southampton's Vice-Chancellor, believes that flip-lectures (not the same as 'online courses' or, indeed, 'free') could '"liberate" students from out-of-date styles of teaching'. He goes on to say that having watched the flip lecture, students and lecturer could then 'convene a discussion in a lecture hall'! Oh, that'll be a lecture, then? Most contemporary in-person lectures I have seen involve, effectively, the lecturer talking and then discussing issues with the students, but, truthfully, there is no one-size fits all model of teaching at institutions internationally. At my university, we use all forms of teaching: traditional lectures, seminars, tutorials, field trips, workshops, online supplementary materials, and flip-lectures. Moreover, "flip-lectures" and these other techniques have been around for years (ask the Open University, or look at Youtube); it's just the audience that has broadened by the openness of the internet.

Nutbeam was joined in discussion by Mark Taylor, the dean of Warwick Business School. He apparently said: 'Seminars and lectures are medieval concepts. They

were introduced in medieval Europe and haven’t changed much in 700 or

800 years.' Oh dear. Where to start with this? It's not accurate of course, but even if it were, so what? Is the implication that not only lectures but seminars should be jettisoned because they're old? They should be scrapped because they're 'medieval'? Hang on! Universities are medieval. Parliament is medieval. Common Law is medieval. Mercantilism is medieval. Towns are medieval. English is medieval.

This use of 'medieval' to suggest something so... what? -- Old-fashioned? Redundant? Useless? Simplistic? -- is vacuous. It is facile. It is, however, potentially damaging to those of us who focus our scholarly and academic efforts on the medieval. So, simply: please, stop it.

Thanks.

Saturday, April 27, 2013

The MLA, Old English and all

MLA President, Marianne Hirsch, wrote to the Old English Division of the Association on 28 March 2013. On behalf of the Executive Council, she asked us the following, among other things: 'Given the disproportionate number of divisions in English in relation to other fields like African and East Asian, would you consider consolidating with Middle English Language and Literature, Excluding Chaucer and with Chaucer? What would such a division be called? Old and Middle English? Early English?' The Old English committee replied that we wanted no such consolidation.

Now, almost a decade ago, I argued for a more nuanced approach to periodization, with its arbitrary categories creating strange literary and linguistic lacunae (http://www.academia.edu/1374101/Editorial). For research purposes, and even for teaching (especially in the undergraduate program), it is useful to cut through swathes of time, to juxtapose and reconfigure in ways that narrower foci of single periods might not obviously permit. Yet, there's a great deal to be said about concentrated study, if that study is framed by peripheral vision.

Still, though, I cannot agree to a request from a professional association to conflate, collapse, concertina a thousand years of English literatures, languages, and cultures into one. The letter that the Division wrote in response (here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/168368943174422/597913600219952/) gave a number of very good reasons to maintain the distinctiveness of Old and Middle English, and all are compelling. One of them, though, has a significance that is easy to miss: it's the #5 in the letter, the 'Professional' reason, which states that 'MLA Divisions in English Literature tend to mirror hiring specialties'. I think, perhaps, that 'mirror' is the most politic way of putting it. I wonder if, in fact, in some economically constrained and resource-light English Departments, the MLA's divisions and trends don't actually contribute to/drive/impel/suggest particular hiring specialties?

For this reason, as well as many others, the MLA has an influence that is actually quite astonishing when one thinks about it (and this is to say nothing of the job lists, which, as a British academic, I find bizarrely centralized in schedule and format, and utterly brutal in implementation). My view of a professional association is that such a body exists principally to encourage a love of its subject and to assist its subject's practitioners; that it seeks to support and defend and lobby; that it helps to provide useful meeting places, tools, and contacts for its members. And that would be all its members: from a hard-core Anglo-Saxonist (whoop!) to a contemporary digital theorist; from an African-American literature scholar to a Slavic linguistics PhD student. All the members, MLA. All of them.

Now, almost a decade ago, I argued for a more nuanced approach to periodization, with its arbitrary categories creating strange literary and linguistic lacunae (http://www.academia.edu/1374101/Editorial). For research purposes, and even for teaching (especially in the undergraduate program), it is useful to cut through swathes of time, to juxtapose and reconfigure in ways that narrower foci of single periods might not obviously permit. Yet, there's a great deal to be said about concentrated study, if that study is framed by peripheral vision.

|

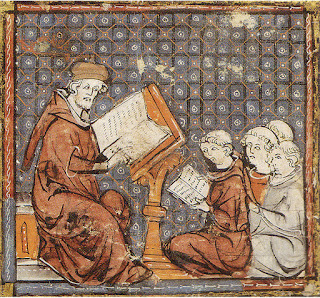

| Salisbury Cathedral Library 150: Gallican Psalter and Gloss |

Still, though, I cannot agree to a request from a professional association to conflate, collapse, concertina a thousand years of English literatures, languages, and cultures into one. The letter that the Division wrote in response (here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/168368943174422/597913600219952/) gave a number of very good reasons to maintain the distinctiveness of Old and Middle English, and all are compelling. One of them, though, has a significance that is easy to miss: it's the #5 in the letter, the 'Professional' reason, which states that 'MLA Divisions in English Literature tend to mirror hiring specialties'. I think, perhaps, that 'mirror' is the most politic way of putting it. I wonder if, in fact, in some economically constrained and resource-light English Departments, the MLA's divisions and trends don't actually contribute to/drive/impel/suggest particular hiring specialties?

For this reason, as well as many others, the MLA has an influence that is actually quite astonishing when one thinks about it (and this is to say nothing of the job lists, which, as a British academic, I find bizarrely centralized in schedule and format, and utterly brutal in implementation). My view of a professional association is that such a body exists principally to encourage a love of its subject and to assist its subject's practitioners; that it seeks to support and defend and lobby; that it helps to provide useful meeting places, tools, and contacts for its members. And that would be all its members: from a hard-core Anglo-Saxonist (whoop!) to a contemporary digital theorist; from an African-American literature scholar to a Slavic linguistics PhD student. All the members, MLA. All of them.

Friday, March 29, 2013

Kindness, caring and criticism: the academic book review

Preambling

The Kalamazoo 2012 Babel session in which a very different version of these thoughts was delivered concerned itself with “finally leaving, getting rid of, abandoning, refusing, and letting go of potentially toxic ‘love-objects,’ with ‘love-objects’ here denoting any possible object: ideological, methodological, disciplinary, textual, art historical,” and so on. My topic was the letting go of the objects/subjects of perfection and superiority. It was about embracing kindness in academia; practicing carefulness; encouraging a sense of self-worth in everyone.

Being an academic is, regardless of how we’re perceived, a difficult job, even though we are deeply privileged to be able to teach, to think our thoughts aloud, and to research what we’re passionate about. The difficulties come from many sources, including the constant pressure throughout a career to sit on an apparent cloud of cleverness, never mind the uncertainty of the profession in this age of cutbacks and cheapskate institutions. I recognize, too, that “difficulties” simply doesn’t cut it for those searching for a permanent position in a world of exploitation, faculty and staff retrenchment, and competition (and as for tenure, that’s another blog, and for what it’s worth, let’s remember that tenure was abolished in the UK in 1988). If it isn’t the RAE/REF that is hounding the British scholar—metering the minutes before the submission of the next article, calculating the merits of a book in unintelligible points (0-4*) before it’s been published—then it’s the tick-tock of the Tenure Timer, battering the Assistant Professor into submission to the system via the monograph—a form of writing that I’ve heard many say has had its day; yet, for most in Arts and Humanities, it lingers on as the measure of scholarly competency. (This obsession with “The Book” has to end, by the way. There should be room for many varied forms of scholarly output, each judged on its own merits.)

Writing a book is, frankly, tricky enough, without the clock, without the pressure from onlookers. For many, writing the first book is a truly stressful and fearful process, with long periods of self-doubt and, in some cases, doubt leading to an intellectual paralysis and the inability to finish the project. To all intents and purposes, finishing something that one can imagine needs to be perfect is almost impossible. Besides, when it’s “finished” it’s still not complete. When I finished my first book—submitted the manuscript, and went out to dinner with my husband to celebrate, he said, helpfully, “But it’s not really finished, is it?” reminding me of the copy-editing, proof-reading, and indexing remaining to be done. That put an damper on the evening. But, even when it is really finished…oh, there’s the reviews. Ah. The reviews.

Spitting Feathers, Splitting Hairs

What do these peer-esteem mechanisms reveal about our field and our profession? Academics, rightly or wrongly, are the arbiters, the authorities, on most “worthy” endeavors—cultural, social, historical, scientific. Indeed, from television and film requests to academics, to grant funding bodies’ requests for review, to tenure recommendations, others external to academic institutions clearly consider this scholarly authority to be credible. The role of arbiter and commentator, most obviously of all, extends to the reviewing of potential publications, too, where presses and journal editors choose reviewers cognizant of the importance of their seal of approval or disapprobation. And while I doubt that the puff on a book jacket would ever make or break a book, a bit of a blessing by a big name cannot go amiss. There are good books, there are bad books (see http://americanbookreview.org/pdf/top40badbooks.pdf for some) and no one denies this, but in the academic world, more (or is it less?) is at stake than “good” or “bad”; scholars who are reviewing have a professional obligation to those whom they review. Thus, the guise of “arbitration” should not be used to provide thin cover for rudeness, sarcasm and personal attack.

The Rhetoric

From a wide choice of reviews, none of which I intend to publicize specifically, though I am happy to give reference details to anyone who wants them, I wonder what motivated the kinds of language used? Reviewers who dislike what they read have a number of interesting tactics (and I am sure there are hundreds more):

1. The rhetorical question, urging the discerning reader to agree with the implied criticism: “Is this really a novel insight?” “Does this author imagine himself to be adhering to scholarly standards?”

2. The personification of the book, where it stands in for the person of the scholar him- or herself: i) “The book is flawed by a pervasive and reckless disregard for historical…facts and issues, and for much of the relevant scholarship in these disciplines”; ii) “[This book] would be highly welcome… if only it would meet moderate scholarly standards”

3. Sarcasm: “[X’s] monograph draws upon and enters into the recent discussions and gives a detailed overview—or as she calls it, ‘a critical study’—of the corpus”

4. Use of anti-intellectual lexis: “amateurish,” “mind-numbing,” “specious”

5. Meiosis (or some such term… what is it?) for diminishing substance yet incremental egregious error: “A few examples must suffice here for illustrating the editor’s pervasive failure to meet such standards. Most basically, there are serious deficiencies throughout in handling secondary literature. I restrict myself here, however, to technical deficiencies...”

6. Implied failure signaled by verbs and adverbs that undermine: “assumes,” “attempts,” “unfortunately”

7. The Critical Paradox: “Because of the outrageous and uncontrolled nature of the speculation which it contains [this book] in this reviewer’s opinion, is unlikely to have any impact whatsoever on the field.” [If it’s unlikely to have any impact, why bother to review it?]

8. Unhelpful ambivalence: “Sincerity is the politeness of the critic, and it is with sympathy (after all the criticism) that this reviewer welcomes the provocative nature and vision of this book, although it claims and concludes far too much from far too little convincing evidence”.

Can any academic really suggest of another that they might write a monograph, willfully abandoning “standards” and being deliberately “reckless”? A desire to show what the reviewer knows to be wrong, without any real attempt to engage with what is right, demonstrates that the review is only partly about the book itself. What creates this sense of indignation in a reviewer is curious: that an author makes mistakes? Give a list of corrigenda. That the author treads on ground that the reviewer knows so much better? The reviewer can write a kindly corrective article. That the reviewer wishes to shame the author? The shame pertains, surely, to the reviewer’s lack of careful collegiality. Moreover, of course, the reviewer proffers an opinion on the overall utility and academic value of the book. In a case above, where the author is accused of a “pervasive disregard” for all that is to be upheld, the very same book won a major prize and was deemed by another reviewer to be “an important book…offering richness for modern scholars.”

Real damage to people’s sense of professional worth can result from hard-worded reviews. This writer here (http://chronicle.com/forums/index.php?topic=89162.0) talks about how hurt their feelings are by the review they’ve just read. While they take on board some of the criticisms proffered, it’s clear that damage is done at a personal level. This isn’t ok; it really isn’t. To be hurtful, to say something in a review that you would not say to that person in a friendly and constructive conversation, is not ok. Reviewers have a responsibility to make their criticisms known, but known kindly, for these same reviewers also have a responsibility to their colleagues and their profession to assist in nurturing and appreciating the work done by those colleagues, often in very trying circumstances. If there is something critical to be said, and reviewers cannot encourage, mentor and gently correct, they should not comment at all. For, as I have said before, having learned it from the great Greg Walker some dozen years ago,

“It’s nice to be important; but it’s more important to be nice.” If we can’t extend that mantra to our colleagues in the field, then there is something wrong with the world in which we work (and it is, after all, just work, just a job).

Thursday, March 21, 2013

That was 'This is Not the End of the Book'

Umberto Eco and Jean-Claude Carriere have co-conversed This is Not the End of the Book,

curated by Jean-Phillipe de Tonnac (NorthwesternUP, 2011 [translated by

Polly McLean]). At 336 pages, it's a long and wide-ranging chat about

books--their role in mostly western culture, their significance to the

discussants, and the manifold ways in which the book contributes to

lives. It isn't, as one might think from the declarative title, a foot-stamping

manifesto in support of the, apparently, fading light of the physical

book, but it does remind us of the ubiquity of the book; its flexibility of form; readers' relationships with their books; and the technology's dogged persistence in the face of multiple persecutions through the centuries.

For Eco, quite simply, books (or scrolls) are 'the emblem of civilisation' (26) and the containers of collective memory (63). For Carriere, the rapid obsolescence of modern media makes the digital pale in comparison with the longevity and robustness of books (31). With books, through archives and libraries (the library as 'an assurance of learning') (284), information can be filtered, sorted and retrieved (67ff.). Moreover, and significantly, this retrievability means that '[o]ur past...is not set in stone. Nothing is more alive than the past' (85). Carriere regrets the loss of the rough draft, the many visible steps en route to the text's completion--the (paradoxical) emergence of the 'phantom version' in the digital era (117).

And for both Eco and Carriere, it is the dynamism and quickness of the book that registers most strongly: 'A great book is always alive; it grows and ages alongside us without ever dying' (158); each reading of a book is different; each experience with an old favourite changes from the last, as we ourselves change. But some readers, it seems, never change or evolve intellectually. Eco and Carriere admit to a fascination with the idiotic and the false, with the bookburners (245ff) and the censors (207ff). 'Studying stupidity', comments Carriere (216), 'challenges the sanctification of the book, [and] reminds us that we're all constantly in danger of spouting similar nonsense'.

There's no nonsense here. This is a delightful book, replete with fascinating, eclectic, learned and trite facts, experiences and musings. Carriere remembers the impressive missals of childhood church services, where 'Truth came out of a book singing' (294); while Eco, decrying the use of toxic chemicals in removing active bookworms, advises keeping 'an alarm clock in your library. The kind our grandmothers used to have. Apparently the regular tick-tock, and the vibrations it sends through the wood, keep the worms in their hidey-holes' (310).

And if that doesn't make a reader want to read this book--knowing that once it's read it, it will be the End of the Book--I don't know what would.

For Eco, quite simply, books (or scrolls) are 'the emblem of civilisation' (26) and the containers of collective memory (63). For Carriere, the rapid obsolescence of modern media makes the digital pale in comparison with the longevity and robustness of books (31). With books, through archives and libraries (the library as 'an assurance of learning') (284), information can be filtered, sorted and retrieved (67ff.). Moreover, and significantly, this retrievability means that '[o]ur past...is not set in stone. Nothing is more alive than the past' (85). Carriere regrets the loss of the rough draft, the many visible steps en route to the text's completion--the (paradoxical) emergence of the 'phantom version' in the digital era (117).

And for both Eco and Carriere, it is the dynamism and quickness of the book that registers most strongly: 'A great book is always alive; it grows and ages alongside us without ever dying' (158); each reading of a book is different; each experience with an old favourite changes from the last, as we ourselves change. But some readers, it seems, never change or evolve intellectually. Eco and Carriere admit to a fascination with the idiotic and the false, with the bookburners (245ff) and the censors (207ff). 'Studying stupidity', comments Carriere (216), 'challenges the sanctification of the book, [and] reminds us that we're all constantly in danger of spouting similar nonsense'.

There's no nonsense here. This is a delightful book, replete with fascinating, eclectic, learned and trite facts, experiences and musings. Carriere remembers the impressive missals of childhood church services, where 'Truth came out of a book singing' (294); while Eco, decrying the use of toxic chemicals in removing active bookworms, advises keeping 'an alarm clock in your library. The kind our grandmothers used to have. Apparently the regular tick-tock, and the vibrations it sends through the wood, keep the worms in their hidey-holes' (310).

And if that doesn't make a reader want to read this book--knowing that once it's read it, it will be the End of the Book--I don't know what would.

Saturday, February 2, 2013

Restrictive 'Humanities'

Hmmm. The Humanities. The Digital Humanities. As a Digital Medievalist, Andrew Prescott said in an email to me today that he has a BA, a Bachelor of Arts degree, not a BHum. We are PhDs, not PhHums. When did the 'Arts' become the 'Humanities'? 'Humanities' are everywhere and nowhere. The study of the 'Human'? Virtually all fields do that in some, even tangential, regard; indeed, 'the proper study of mankind is man' [and woman], as Pope helpfully reminds us.

The definition of 'humanities' is shifting again. From its origins in English as a translation of humanitas, where 'humanness' was denoted (in the late fourteenth century Wycliffe Bible: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/m/mec/med-idx?type=id&id=MED21446), to its specificity in the educational ideal of Studia Humanitatis, to its current ubiquity, the word has formed the focus of lengthy and detailed scrutiny. In 'Renaissance Humanism and the Future of the Humanities', Literature Compass 9/10 (2012), 665-78 (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/%28ISSN%291741-4113), Jennifer Summit traces the origin of the Humanities to the Renaissance, publicising the utility of Renaissance scholarship for the current debate, pointing out that 'No more is "the human" the unique commitment of the humanities' (667), but that the Renaissance transformation of education still has lessons for contemporary academe. The trends that she discerns are temporally assigned to the fourteenth century when 'the unprecedented expansion of lay literacy and education across Europe...made the studia humanitatis a mechanism for both socializing the rising literate classes and sorting them into appropriate stations' (671).

In their recent Short Guide to Digital_Humanities (available as a stand-alone PDF here, taken from their book: jeffreyschnapp.com/short-guide-to-the-digital_humanities), Anne Burdick, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner and Jeffrey Schnapp offer an interpretation of 'humanities' that confirms the post-medieval definition offered by Summit. 'For nearly six centuries,' they say, 'humanistic models of knowledge have been shaped by the power of print as the primary medium of knowledge production and dissemination'. This equation of the humanities with the dawn of print, or with the Renaissance more specifically, is unhelpful.

In their recent Short Guide to Digital_Humanities (available as a stand-alone PDF here, taken from their book: jeffreyschnapp.com/short-guide-to-the-digital_humanities), Anne Burdick, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner and Jeffrey Schnapp offer an interpretation of 'humanities' that confirms the post-medieval definition offered by Summit. 'For nearly six centuries,' they say, 'humanistic models of knowledge have been shaped by the power of print as the primary medium of knowledge production and dissemination'. This equation of the humanities with the dawn of print, or with the Renaissance more specifically, is unhelpful.

First: the dawn of print did not displace, and still has not displaced, the manuscript; indeed, the digital age itself has not done so, and, I venture, will never do so. Most of my students still take notes, even though I am quite happy for them to use tablets and laptops; in the 'modern' era, James Joyce wrote with a pen (see left); the Beatles Lyrics are manuscript; Seamus Heaney's evocative translation of Beowulf exists in hybrid form--as typescript with manuscript emendations, corrections and expansions. The age of the manuscript, then, is still with us, and very much in vogue with large numbers of students wanting to study palaeography, calligraphy, and book-making, and with the 'handwritten' object or the celebrity autograph in huge demand, and demanding increasingly exorbitant prices.

| |

| Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ashmole 1462, ff. 9v-10v |

The definition of 'humanities' is shifting again. From its origins in English as a translation of humanitas, where 'humanness' was denoted (in the late fourteenth century Wycliffe Bible: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/m/mec/med-idx?type=id&id=MED21446), to its specificity in the educational ideal of Studia Humanitatis, to its current ubiquity, the word has formed the focus of lengthy and detailed scrutiny. In 'Renaissance Humanism and the Future of the Humanities', Literature Compass 9/10 (2012), 665-78 (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1111/%28ISSN%291741-4113), Jennifer Summit traces the origin of the Humanities to the Renaissance, publicising the utility of Renaissance scholarship for the current debate, pointing out that 'No more is "the human" the unique commitment of the humanities' (667), but that the Renaissance transformation of education still has lessons for contemporary academe. The trends that she discerns are temporally assigned to the fourteenth century when 'the unprecedented expansion of lay literacy and education across Europe...made the studia humanitatis a mechanism for both socializing the rising literate classes and sorting them into appropriate stations' (671).

In their recent Short Guide to Digital_Humanities (available as a stand-alone PDF here, taken from their book: jeffreyschnapp.com/short-guide-to-the-digital_humanities), Anne Burdick, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner and Jeffrey Schnapp offer an interpretation of 'humanities' that confirms the post-medieval definition offered by Summit. 'For nearly six centuries,' they say, 'humanistic models of knowledge have been shaped by the power of print as the primary medium of knowledge production and dissemination'. This equation of the humanities with the dawn of print, or with the Renaissance more specifically, is unhelpful.

In their recent Short Guide to Digital_Humanities (available as a stand-alone PDF here, taken from their book: jeffreyschnapp.com/short-guide-to-the-digital_humanities), Anne Burdick, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner and Jeffrey Schnapp offer an interpretation of 'humanities' that confirms the post-medieval definition offered by Summit. 'For nearly six centuries,' they say, 'humanistic models of knowledge have been shaped by the power of print as the primary medium of knowledge production and dissemination'. This equation of the humanities with the dawn of print, or with the Renaissance more specifically, is unhelpful.First: the dawn of print did not displace, and still has not displaced, the manuscript; indeed, the digital age itself has not done so, and, I venture, will never do so. Most of my students still take notes, even though I am quite happy for them to use tablets and laptops; in the 'modern' era, James Joyce wrote with a pen (see left); the Beatles Lyrics are manuscript; Seamus Heaney's evocative translation of Beowulf exists in hybrid form--as typescript with manuscript emendations, corrections and expansions. The age of the manuscript, then, is still with us, and very much in vogue with large numbers of students wanting to study palaeography, calligraphy, and book-making, and with the 'handwritten' object or the celebrity autograph in huge demand, and demanding increasingly exorbitant prices.

Secondly, to associate the origin of Studia Humanitatis with the Renaissance is to risk overstating the 'dawn of modernity' theory that underpins Stephen Greenblatt's contentious book, The Swerve (on which, see my previous blog, and see http://www.inthemedievalmiddle.com/2012/12/stephen-greenblatts-swerve-and-mlas.html). Let's be clear that the 'humanities', as defined under Studia Humanitatis in the Renaissance, derived from the Medieval curriculum--the Trivium, in particular (see Paul Oscar Kristeller,

Renaissance Thought

II: Papers on Humanism and the Arts [NY, 1965],

p. 178). Medieval scholars, students, thinkers, writers--people--were not some antiquated and utterly unlike-us body of beings. The Medieval is not set apart from the Renaissance by some thickly-drawn line of differentness.

Our desire to situate ourselves historically, to explain how we have come to where we are, to think through how we can compare text technological 'revolutions' like the manuscript-to-print, print-to-digital shouldn't blinker us to the full story that history offers. It shouldn't suggest a yearning to disguise the long march of humanity--the really longue durée--, to exclude (tiresomely, yet again) a whole millennium of rich, meaningful and pertinent textual cultures in the Medieval period. And this is only the tip of a global iceberg often missed in these debates claiming academic ground; these debates also, too frequently, preclude the astonishing contribution of Eastern and Islamic cultures, among many others, that properly belong to 'Humanities', Digital or Otherwise. Instead of restricting what 'humanities' does or doesn't mean, then, it is time for generous, capacious and welcoming methodologies and definitions that seek to include, temporally and spatially, rather than exclude.

Sunday, January 27, 2013

What's in a Name?

‘A name is the first

and final marker of individual rights, one fixed part of the ever-changing

human world. A name is the most basic characteristic of our human rights; no

matter how poor or how rich, all living people have a name, and it is endowed

with good wishes, the expectant blessings of kindness and virtue.’

Ai Weiwei

Perhaps a half-a-mile separates the Vietnam Memorial in The

Mall in Washington D.C. and the memorial to the students killed by the Sichuan

earthquake in China in 2008. The former, by Maya Ying Lin, sits unobtrusively

in the west end of the Mall, while Ai Weiwei’s installation, ‘Remembrance’, is

a temporary exhibit in the Hirshhorn Museum, further east towards the Capital.

Both memorials are extraordinary testimonies to the tragic loss of human life

in recent decades, and both, in very distinct ways, are intensely moving. From

a text technological perspective the differences are obvious and notable: the

Vietnam Memorial is discreet and yet absolutely public, created from black durable

granite, with sandblasted inscribed names.

Weiwei’s monument to the crushed students is materially

ephemeral: it is ink-jet printed onto smooth, matt paper and takes up an entire

wall of the Hirshhorn’s first floor, placed (surely strategically) as people

come up the escalator. Hardly anyone stopped to look at it. As I came up the

escalator, I assumed it was a list of donors to the museum, so I didn’t bother

to examine the wall more closely. There was some kind of voice in the

background, but this didn’t register, either.

On the way down from the second

floor, having seen Weiwei’s work, then, then I stopped to look. ‘Remembrance’

is transient and a surrogate for the ‘real’ list that resides permanently in

Weiwei’s workshop. It is public and yet private—huge but indoors, utterly visible

and yet easily missed. It shares this missableness with the Vietnam Memorial,

though the fame and cultural relevance of the latter draw people

to it. The Vietnam Memorial is permanent, monumental, reflective (and a place

for reflection), where the inscriptions can be touched and literally entered

into by the fingers of those searching for the traces of a loved one. The

smooth polished surface of the granite reflects the park behind it and the

shapes of those who pass by. In this way, viewers become part of the tragedy,

if only temporarily; and the world goes on both around and within the memorial,

reminding everyone of the transitory nature of life.

| |

Both memorials use the sweep of their respective landscapes

to suggest unendingness and extensity of perspective. The Vietnam Memorial with

its angular centre (see photo 1) where the end of the war (1975) meets the beginning (1959)

is ten feet tall at this central point, but decreases in height as it moves

away in two directions. This amazing sight of the diminishing perspective

enhanced by diminishing size suggests the interminable nature of man’s feuding.

Weiwei’s monument seems to use the gentle curved sweep of the Hirshhorn’s

rounded architecture to fade into an indefinable end. The overall effect is

enhanced by the juxtaposition of the suddenness and brutality of the students’

deaths with the smoothness (efficiency of the state?) of the paper material and

the monument’s positioning.

Numbers are significant. They underscore the enormity (in

both its traditional and more recent meanings) of lost life. The veteran

gentleman who stands at the vertex of the Vietnam Memorial answered three

people’s questions--‘How many names are here?’--in the few moments that I stood

close to him. I asked him what question he is asked most often. ‘How many

died’, he replied. ’58,282’. This is twenty-six more names than are accounted

for in the information leaflet for the Memorial. This is thus an eventful text,

a fluid text. As the names of those missing-in-action, introduced by a cross,

are transformed into the names of those known to have died, the cross is

transformed into a diamond. Should those listed as missing-in-action ever be

found alive, the cross would be surrounded by a carved circle.

Weiwei’s eventful text is added to as the names of victims

are discovered by the investigators. His looks like the clinical exercise of

the registrar at a big event. The tabulated listing could be mistaken for some

form of spreadsheet counting exercise, until one looks more closely and the horror of the list is revealed by its scale.

The Vietnam Memorial,

meanwhile, also uses a sense of proportion to shock: the first 1959 granite

panel contains the names of those lost over six years; the second panel, the

names of those lost over five months; the third panel, those lost over five

weeks. That visual escalation of war is shocking; the accumulation of black and

white detail in Weiwei’s memorial, similarly so. Both are overwhelming.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)