At the exhibition of the St Albans

Psalter and Canterbury stained glass, hosted by the Getty Museum from September 20, 2013 to February

2, 2014 (http://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/canterbury/), the curators claim that ‘By uniting the intimate art of book illumination

with monumental glass painting, this exhibition explores how specific texts,

prayers and environments shaped the medieval viewer’s understanding of these

pictures during the period of artistic renewal following the Norman Conquest of

England’ (blurb on board at entrance wall). Pace

the facts that 'prayers' are 'texts', that it was more than England that the Normans conquered, and

there was never a diminution of English artistic achievement such that ‘renewal’

was required, the focus on ‘these pictures’ should have been a warning of what

was coming as I turned the end of the wall to face the first room. First,

though, I had to pass another board that mistakenly claimed: ‘[In 1066] Latin

replaced English as the written language used in government and religious

life’. First, Latin had always been used in government and religious life;

secondly, it did not replace English,

especially in ‘religious life’; thirdly, why do the curators feel it necessary

to ameliorate their exhibit by diminishing social and cultural accuracy? Why not

reflect a more nuanced historical reality?

|

| Front Steps of The Getty |

What is really missing at the

exhibition, though, is that which claims to be present: the St Albans Psalter itself

(or, indeed, complete stained glass). In a provocative display, the curators

choose to maximize the literal spread of the codex by utilizing its current disbound

state to disperse bifolia through the four large, high-ceiled rooms, dimly lit

and ideologically impelled. Most curious is the decision to show bifolia in

separate wooden frames, categorized in sections by various labels like ‘Text

Page’ (containing the Alexis Quire, as if only those

folios have ‘text’). These exhibited bifolia are obviously conjugate pairs of leaves,

but since many are outer bifolia, this means that only very rarely does one

observe what would be an actual opening in the properly assembled and bound

book. Successive folios representing what a medieval viewer might have seen are

infrequent and the book is thus turned into a dismembered spectacle,

displayed in component parts (like the Calendar, which is shown out of

monthly order). The book is made extensive, but its functional extensity

is utterly elided.

This is understandable in some

respects, since spread-out like this, many folios are available for viewing by

many viewers simultaneously. A touchscreen reproduction of one opening, which is itself encased adjacently, allows the

reader to move around the virtual page with a cursor, with a neat function to allow

simultaneous translation of the Latin. A facsimile of the St Albans Psalter sits

on a lectern against a sidewall for the assiduous attendee, but there is

otherwise little left of the bookness of the book. Moreover, unhelpful

juxtapositions mislead or make convenient connections that cannot be

chronologically, generically or thematically justified. Thus, for instance, for

no apparent reason, two leaves of the Eadwine Psalter’s prefatory cycle (owned

now by the Pierpont Morgan, though more properly belonging with the unmentioned

Cambridge, Trinity College R. 17. 1) appear at the exhibit’s margins,

marginalized, against separate walls with little connection made between these

and St Albans’ deconstructed quires.

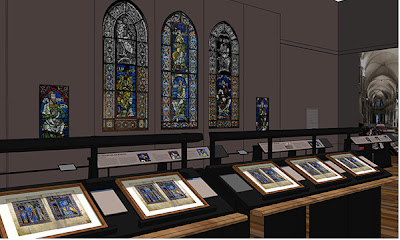

The first three of the large rooms

are deliberately made to emulate sacred space; the stained glass (with two

black-and-white supply panels) overlooks the fragmented Psalter, but does not connect with it in any meaningful way.

Situated in front of the glass are long benches, like church pews, and this

ecclesiastical setting is continued in oversized pictures (a cloister photograph

covers the end wall in the second room, for example; and Canterbury Cathedral’s

East End sits to the right of the stained glass).

|

| Digital Image from http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/getty-voices-designing-canterbury-and-st-albans/ |

Why did this seem like a good

idea? Why is this hyperreal immersion, this pretend churchi-ness,

appropriate? The third room—loosely about saints and Thomas Becket—proffers

more forced connections: manuscripts with tentative links to Becket or showing

the same artist as one of those in the St Albans Psalter are juxtaposed with a

pilgrim badge, a Limoges reliquary, another reliquary casket and a liturgical

comb carved with Henry II and Becket. Perhaps I didn’t read carefully enough in

this room, but the theme of saints’ cults is oddly attached to two sets of

texts (the Psalter and the windows) that are concerned with saints in far more

complex ways than are suggested here. A more obvious connection might have been

salvation.

The final room is explicatory and by

far the clearest part of the exhibit. Cases demonstrate how medieval

illumination was produced and how stained glass is made. It’s a good final

reminder that in this exhibition we are dealing with real objects that have

multiple functions. The Psalter and the stained glass are not just pictures. There is so little emphasis on

word-text in the case of the Psalter that one would be forgiven for forgetting

the Book of Psalms is all about the text (said, sung, read, memorized). The

real object is displayed at The Getty, ironically, as if it were digital—chopped up into its

consistent parts, browsable in no defined order. And while it is a wonderful

opportunity to see up close the details of the manuscript’s folios, one wonders

what impression modern viewers are left with of this rather lovely, but here

entirely decontextualised, set of materials.

Elaine, I find this entry lovely and sad, much like my own standard operating disposition on these interesting questions—bittersweetly exciting and concerning. The last sentences of your essay here poke at something that’s been bugging me for a few years: ‘The real object is displayed at The Getty, ironically, as if it were digital—chopped up into its consistent parts, browsable in no defined order. And while it is a wonderful opportunity to see up close the details of the manuscript’s folios, one wonders what impression modern viewers are left with of this rather lovely, but here entirely decontextualised, set of materials.’ I couldn’t say anything better or more evocative, but it is the ‘as if’ and the modern viewers’ ‘impression’ that are remarkable. The Getty is providing a kind of mediated access to the book—an amazing opportunity to see it up close, in detail (in ways no medieval reader would access it)—and yet the book has become a kind of atomized dispersal of screens. The Getty fundamentally has made the physical book a virtual one, and as more and more books become digitally available—ubiquitous, accessible, shimmering so (not) close before our eyes—the pressures and drive of the general narrative (faulty and overly simplified as it is) that the digital suffices or supercedes the actual seems to be confirmed: an impression one might take away is that the medieval book works ‘as if’ it were a digital one. That this is materially posited by such a prestigous institution only reinforces the need—so well addressed here by you—to at the very least think hard about what we are doing when we digitize books and other aesthetic objects that depend so much on their physicality, corporeality, and tangibility for a great deal of their historical meaning.

ReplyDelete