TEXT is art, words, symbols, code. It is the object, the artefact, that contains the communication. Manuscript books or fragments, in their entirety, are examples of TEXT and the object of study (obviously) of Text Technologies. More provocatively, perhaps, bodies carrying tattoos--whether Maori tattoo, or celebritized longitude/latitude patterns--might be examples of TEXT; in this case, code which signifies either something particular to the person or, more broadly to a social group. To fill the space of the skin with tattoo is to participate in textual production that was, until recently, considered subversive. The intelligibility of tattoo depends on the wearer's decision about how public they want their body text to be. Some seem semantically transparent:

And others require significant interpretative work on the part of the onlooker:

Akin to tattoo in its intentional subversiveness is graffiti. Hidden beneath the swirls and curls of the tagged letters is the name of the graffiti artist ('artist'?), exclusive to those in the know:

And here, again, space is filled by a deliberately obfuscatory message, a text technology where the entire context provides textness; where the precise location and substrate are key to the type of communication being imparted; and where it's usually singularly important not to be able to read the text.

Thoughts on the textual and literary, & on text technologies from Babylonian cuneiform to Twitter, with an eye on the medieval

Friday, October 26, 2012

Thursday, September 27, 2012

When is a Text not a Text?

We've been discussing 'Text' again in class, as part of 'Text Technologies: A History'. So, we pondered when is a Text not a Text? When it's anything except words, which are always 'text'. But we'll only allow words as long as the words are definable as such--as words. That is, they cannot be random markings or even structured-but-uninterpreted markings, since markings that have no discernible meaning cannot be 'text', because they don't mean anything and 'text' must have meaning. (One should surely argue here that meaning is not a one-way street; I can produce text with meaning to me, even if no one else has a clue what I'm talking about. And besides, meaning is always subjective.) Or, ok, not 'words' per se, but symbols; symbols constitute 'text'. Such a definition permits us to include ideographs or pictographs as 'text', except these are, to all intents and purposes, images, and we don't want to allow images as 'text'. Or do we? If something can be read, if something is open to interpretation in a social act of communicative intent, then presumably it is text, even if that thing being read has nothing verbal in it or around it; it is simply a photograph or picture.

Friday, August 31, 2012

One-eyed monsters in the desert

|

Morongo Hotel and Spa, Cabazon, CA (actually in the desert) |

This is not an advertisement advocating the benefits of the desert casino and spa. On the contrary, on our drive from Tallahassee, FL to Stanford, CA, this building was the most monstrous sight we encountered. In terms of the landscape as text--the thread of this and the previous blog--this hideous spectacle might be read as an attempt to conquer the desert that is ultimately testimony to the human's capacity to spoil. It's much more complicated than this, though, since the Morongo band of Native Americans, whose land this is, are the owners of this casino resort. In addition, the construction company claims the resort was 'inspired by the forces of nature and is intended to bring a piece of paradise to the desert' (http://california.construction.com/projects/04_BestOf/casino_morongo.asp). Still, reminiscent of ancient monsters, many of whose characteristics reappear through the imagination of Russell T. Davies in Dr Who and other sci-fi series, from the I-10 road, this hotel bestrides its desert setting like a concrete cyclops, or better still, medieval Blemmyae.

|

Blemmyae from British Library manuscripts (see http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/medieval/monsters/medievalmonsters.html) |

Blemmyae, acephalous monsters with their faces on their chests, were strange and frightening, living with other alien creatures in distant lands. In the Old English Wonders of the East in London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A. xv (the Beowulf-manuscript), these chest-faced beings are said to be eight feet tall and eight feet wide and living on an island with dragons that are 150 feet long. These overlarge monsters, dominating their landscape, are the stuff of fantasy--until one comes across the Morongo reality on the I-10, near Palm Springs.

One can hardly talk about medieval monsters without reference to Jeffrey Jerome Cohen's 'Monster Culture (Seven Theses)', published in Monster Theory: Reading Culture, ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 3-25. He comments that 'The habitations of the monsters (Africa, Scandinavia, America, Venus, the Delta Quadrant--whatever land is sufficiently distant to be exoticized) are more than dark regions of uncertain danger: they are also realms of happy fantasy, horizons of liberation'. In the case of Morongo, it seems that a place of uncertainty--the desert--is transformed into a locus amoenus, a pleasant place, by the construction of the monstrous: a huge watch-tower with its glass eye guarding over the landscape, attempting, perhaps, to suppress, tame it, change its inhospitable nature. I find the one-eyed building sinister and ineffably ugly, but it brings money to the Reservation, allowing the Morongo band of Native Americans to make viable economic use of the parcel of land they were left with.

And yet.

Yet, in a larger sense, Casino Morongo fails to dominate. It's certainly startling as it rears up on the side of the I-10 (rightly winning the I-10 journey prize of 'most hideous'); but, as the photograph taken by Roy Randall on Flickr so ably demonstrates, this concrete carbuncle is nothing in comparison to the landscape it seeks to cultivate:

| |||

| Casino Morongo from the mountains (http://www.flickr.com/photos/zeroy/2977965265/) |

From a distance, the Casino becomes a speck, just another trace of passers-through. From this distance, the Casino Hotel is little more obvious, indeed, than the petroglyphs, carved millennia ago, in the Coyote Hole rocks near Joshua Tree, earlier marks left by those for whom this wilderness was home.

Friday, August 17, 2012

Landscape as Text

As a family (husband, two children, two dogs, one cat), we very recently drove across America, so that I could take up my new post as Professor of English at Stanford University, south of San Francisco. Our 2,600 mile journey along the I-10 and up the I-5 from Tallahassee, Florida to Stanford took five days, my husband and I each driving a car. I drove the thirteen-year old Honda CRV, adding considerably to its 111,000 mileage and I had the pleasure of my son's company, together with that of the two dogs.

As we made our way cross-country, taking in West Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California along the way, I became deeply conscious of the ways in which we can read the landscape, both through its natural splendour and through the ways in which it has been colonised by modern American society. I'm sure it's very last century to think of everything as potentially interpretable--that is, potential text--but still, as I say, I was struck by what I could read about this vast country, simply by passing through it. So, this blog and the next few will focus on the things we saw and how these might signify something or other. I'll do this through a sequence of selected superlatives, beginning with the weirdest sight (of many weird sights).

Driving through Eastern Arizona from New Mexico to Tuscon was a sequence of unpredictabilities: skirting desert thunderstorms, but nevertheless being rained upon; high-ish mountain transforming into bouldered panoramas; and soldier cacti standing in battalions on hillsides. Together, these created a visual smorsgabord. It quickly became our favourite few hours in the cars and there'll be more on these sights later. Leaving Tucson, though, we saw the oddest thing; so strange was it that it demanded a rapid set of double-takes, and shrieks of 'Get a photo! Get a photo!' On our right on the westbound I-10, a few miles outside Tucson, was a six-foot (?) cardboard baby sitting in the desert with a cardboard tractor. Like some kind of bizarre mirage, this strange vision of a child at play was utterly incongruous, totally out of context, a doodle literally marginal to the road that demanded to be interpreted, but provided no clues about its purpose.

Unfortunately, the photograph we took really can't capture the weirdness of this prelapsarian baby scene:

There is no explicatory sign, no interpretative board. It suggested vulnerability: a warning, perhaps, that in the desert, the helpless will die? Or was it a billboard for some advertiser, where the text had falled into disrepair? We wondered for some time what this could possibly intimate. When I mentioned it to my husband, who had been driving right in front of us, he confessed he had not seen it at all (eyes on the road, rather than gazing around: good driving). Yet, of course, the board baby is easily found through a Google search using the terms 'giant baby I-10 Tucson'. On this site (http://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/2411?offset=5), I discovered the baby is not six-feet tall; rather, it is TWENTY feet tall. The lack of any proportion or perspective is such a great trick enhanced by the desert setting. Moreover, it is not some strange, dilapidated act of a tractor company; it is the work of the mural artist, John Cerney, completed in 1998 (see http://www.johncerney.com/photogallery.html). I might add that in the image on Cerney's website, you can clearly see a now-missing farmer running away from the baby. The work was originally intended to act as a marker for an educational farm situated just off the interstate. The farm was closed in 2004, so now the marker has nothing to mark; the referent has no reference; signifier without signified. Half a sign. Instead of indicating anything, then, the big baby just sits there, surprising interstate motorists and begging observant passers-by to try and describe what on earth they think they've just seen.

As we made our way cross-country, taking in West Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California along the way, I became deeply conscious of the ways in which we can read the landscape, both through its natural splendour and through the ways in which it has been colonised by modern American society. I'm sure it's very last century to think of everything as potentially interpretable--that is, potential text--but still, as I say, I was struck by what I could read about this vast country, simply by passing through it. So, this blog and the next few will focus on the things we saw and how these might signify something or other. I'll do this through a sequence of selected superlatives, beginning with the weirdest sight (of many weird sights).

Weirdest of Weird Sights

Driving through Eastern Arizona from New Mexico to Tuscon was a sequence of unpredictabilities: skirting desert thunderstorms, but nevertheless being rained upon; high-ish mountain transforming into bouldered panoramas; and soldier cacti standing in battalions on hillsides. Together, these created a visual smorsgabord. It quickly became our favourite few hours in the cars and there'll be more on these sights later. Leaving Tucson, though, we saw the oddest thing; so strange was it that it demanded a rapid set of double-takes, and shrieks of 'Get a photo! Get a photo!' On our right on the westbound I-10, a few miles outside Tucson, was a six-foot (?) cardboard baby sitting in the desert with a cardboard tractor. Like some kind of bizarre mirage, this strange vision of a child at play was utterly incongruous, totally out of context, a doodle literally marginal to the road that demanded to be interpreted, but provided no clues about its purpose.

Unfortunately, the photograph we took really can't capture the weirdness of this prelapsarian baby scene:

There is no explicatory sign, no interpretative board. It suggested vulnerability: a warning, perhaps, that in the desert, the helpless will die? Or was it a billboard for some advertiser, where the text had falled into disrepair? We wondered for some time what this could possibly intimate. When I mentioned it to my husband, who had been driving right in front of us, he confessed he had not seen it at all (eyes on the road, rather than gazing around: good driving). Yet, of course, the board baby is easily found through a Google search using the terms 'giant baby I-10 Tucson'. On this site (http://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/2411?offset=5), I discovered the baby is not six-feet tall; rather, it is TWENTY feet tall. The lack of any proportion or perspective is such a great trick enhanced by the desert setting. Moreover, it is not some strange, dilapidated act of a tractor company; it is the work of the mural artist, John Cerney, completed in 1998 (see http://www.johncerney.com/photogallery.html). I might add that in the image on Cerney's website, you can clearly see a now-missing farmer running away from the baby. The work was originally intended to act as a marker for an educational farm situated just off the interstate. The farm was closed in 2004, so now the marker has nothing to mark; the referent has no reference; signifier without signified. Half a sign. Instead of indicating anything, then, the big baby just sits there, surprising interstate motorists and begging observant passers-by to try and describe what on earth they think they've just seen.

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

Fragmenting the Past through Dispersing Collections of Books

Joseph Mendham, a nineteenth-century Anglican writer, 'controversialist' and book-collector, has been in the news today, as the subject, happily for him, of controversy. It was announced that the UK's Law Society, which owns his extant collection of books and manuscripts, has decided to sell off some of the more valuable items in their possession, despite an agreement apparently made with the original donor to keep the collection intact. The collection is housed at Canterbury Cathedral, with its close links to the University of Kent. Commenting on this sequence of events, Dr Alixe Bovey, at the University of Kent, said in a press statement that 'The imminent removal of the most valuable items will cause irreparable

damage to the coherence and richness of this historic collection' (http://www.kent.ac.uk/news/stories/mendham-collection/2012). Bovey later evocatively observed on her Twitter account that the 'appreciative noises' made by the Sotheby's employees sent to collect the choicest books were 'wincingly excruciating'.

Can the deliberate dispersal of an historic collection of textual materials, carefully and focusedly assembled by an individual or corporate collector, be justified? The Law Society says it needs the money, and will hold off auction until November 1, but why sell off bits of the collection like this? I met a man in 2006 (let's call him Tim, because that was, indeed, his name), who, on hearing that I work with manuscripts, told me proudly that he and a partner in Tallahassee spent a great deal of their time buying up large, intact collections of nineteenth-century US Civil War documents that they managed to procure at bargain prices. (So far, so good.) They did this with the sole intention of dismembering these collections to maximise their profit. (Not so good.) I asked him if they at least provided evidence of the provenance of these documents, so that, should fortune favour the old, the collection might one day be reassembled. Tim had no idea what I meant; he had never given such an historically-aware approach the least thought.

Profiteering in this way by deliberately fragmenting historical evidence of the passions and pursuits of earlier collectors impoverishes our human record. It's that simple. I would liken it to the more explicit lack of intellectual integrity of the St Petersburg Antiquarian Book-Dealer I spoke to once, who sells manuscript leaves on EBay for significant financial gain. Selling manuscript leaves is no crime, but when these come from a whole manuscript sliced into the smallest possible sellable part, it should be. At best, it's unethical; at worst, cultural vandalism. Societies, book-sellers, EBay scourers should at the very least have the decency to seek profit by maintaining the intactness of a cogent collection or a single manuscript, or they are actively destroying what they ironically seek to benefit from.

Can the deliberate dispersal of an historic collection of textual materials, carefully and focusedly assembled by an individual or corporate collector, be justified? The Law Society says it needs the money, and will hold off auction until November 1, but why sell off bits of the collection like this? I met a man in 2006 (let's call him Tim, because that was, indeed, his name), who, on hearing that I work with manuscripts, told me proudly that he and a partner in Tallahassee spent a great deal of their time buying up large, intact collections of nineteenth-century US Civil War documents that they managed to procure at bargain prices. (So far, so good.) They did this with the sole intention of dismembering these collections to maximise their profit. (Not so good.) I asked him if they at least provided evidence of the provenance of these documents, so that, should fortune favour the old, the collection might one day be reassembled. Tim had no idea what I meant; he had never given such an historically-aware approach the least thought.

|

| Jumble |

Profiteering in this way by deliberately fragmenting historical evidence of the passions and pursuits of earlier collectors impoverishes our human record. It's that simple. I would liken it to the more explicit lack of intellectual integrity of the St Petersburg Antiquarian Book-Dealer I spoke to once, who sells manuscript leaves on EBay for significant financial gain. Selling manuscript leaves is no crime, but when these come from a whole manuscript sliced into the smallest possible sellable part, it should be. At best, it's unethical; at worst, cultural vandalism. Societies, book-sellers, EBay scourers should at the very least have the decency to seek profit by maintaining the intactness of a cogent collection or a single manuscript, or they are actively destroying what they ironically seek to benefit from.

Tuesday, July 17, 2012

You have to hand it to 'text'

A book like Cambridge, Trinity College, R. 17. 1, unlike the St Cuthbert Gospel, recently acquired for the nation by the British Library (http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2012/05/the-st-cuthbert-gospel-the-story-of-a-book.html) could hardly claim to be hand-held technology. It is large and unwieldy, weighing at least 20lbs. Also known as the Eadwine Psalter (Google it for lots of images of the eponymous 'prince of scribes' who might have designed the volume) or the Canterbury Psalter, it is one of the most magnificent manuscripts in a century of unparalleled biblio-magnificence. It is half a metre tall and comprises one animal skin per opening and its size means that the reader really has to stand to be able to take in the fullness of the book's folios. If the reader is sitting while examining the volume, most of the upper part of the folio is effectively unreadable. So, the book is not easily used, not easily accessible, and certainly not portable in the way the Cuthbert Gospel is. These manuscripts are the medieval equivalents, in physical terms, of the modern paperback (the little Gospel) and the now non-existent print version of the Oxford English Dictionary (the large Psalter).

And yet, while looking closely at the Eadwine Psalter a couple of weeks ago, even while noting the absence of browsers' marks or the interventions of engaged readers, it became clear to me that to an extent this volume was hand-held--time and time again. Moreover, those hands and their literal imprints are very revealingly and entirely haptically presented on every recto of every folio through the cloth-like nature of the membrane in these handled areas, rather than the stiffer composition of the less handled parts of the leaf. What looks like blankness in the expanse of margin at the foot of the folio (well, blank except for the modern foliation) is anything but, then.

And here, of course, the work of art historians like Jennifer Borland and Kathryn Rudy ('Violence on Vellum: Saint Margaret’s Transgressive Body and Its Audience', in Representing Medieval Genders and Sexualities in Europe: Construction, Transformation, and Subversion, 600–1530, eds. Elizabeth L’Estrange and Alison More [Ashgate, 2011] and 'Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer', Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, Vol. 2, 1 [2010], respectively) helps us to interpret the evidence for how users interacted with books, often very physically, leaving dirt or erasure behind them through their touching of the book.

But less than dirt or rubbing, I am especially interested in those spaces that appear to be blank, particularly when a folio is viewed as a digital image. Here, it is often the voluminousness, the heft, of a book's materiality that is lost to sight. Within this 'voluminousness', the light and shade, the ebb and flow, the rise and fall of the physical leaf is critical to understanding how the book was received by readers, users, casual passers-through. This is felt most obviously in the fabric of the book and is an integral part of the book's textness, its plenitext.

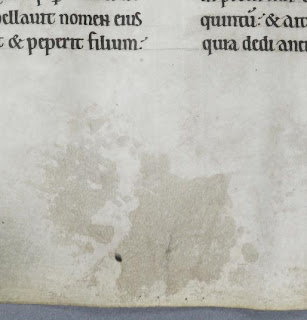

A second example demonstrates this perfectly and illustrates that even the largest of books can be thought of as hand-held technology. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 2, the substantial Bury Bible, produced in the first half of the twelfth century and now divided into three huge volumes, measures 522mm x 360mm. It was a display volume intended among other things to demonstrate the wealth and authority of the Abbey at Bury St Edmunds. But its de luxe quality did not preclude it from being read; its status might only have added to the moment that a reader had with it, for in this book, every verso of every folio bears the physical testimony of use, even if it's difficult to detect. So intense is the turning of the folio that on some versos, the touch of the successive users' hands has left visible proof of their presence through the abrasion of layers of the membrane:

Blankness here, then, is anything but, and what looks like a stain in the digital image is, in fact, the erasure caused by countless page turnings. Thus, while the manuscript itself may be the antithesis of hand-held technology, to turn the folio is, even so, to hold the hands of readers from centuries past.

And yet, while looking closely at the Eadwine Psalter a couple of weeks ago, even while noting the absence of browsers' marks or the interventions of engaged readers, it became clear to me that to an extent this volume was hand-held--time and time again. Moreover, those hands and their literal imprints are very revealingly and entirely haptically presented on every recto of every folio through the cloth-like nature of the membrane in these handled areas, rather than the stiffer composition of the less handled parts of the leaf. What looks like blankness in the expanse of margin at the foot of the folio (well, blank except for the modern foliation) is anything but, then.

|

| Cambridge, Trinity College, R. 17. 1, folio 107r |

And here, of course, the work of art historians like Jennifer Borland and Kathryn Rudy ('Violence on Vellum: Saint Margaret’s Transgressive Body and Its Audience', in Representing Medieval Genders and Sexualities in Europe: Construction, Transformation, and Subversion, 600–1530, eds. Elizabeth L’Estrange and Alison More [Ashgate, 2011] and 'Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer', Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, Vol. 2, 1 [2010], respectively) helps us to interpret the evidence for how users interacted with books, often very physically, leaving dirt or erasure behind them through their touching of the book.

But less than dirt or rubbing, I am especially interested in those spaces that appear to be blank, particularly when a folio is viewed as a digital image. Here, it is often the voluminousness, the heft, of a book's materiality that is lost to sight. Within this 'voluminousness', the light and shade, the ebb and flow, the rise and fall of the physical leaf is critical to understanding how the book was received by readers, users, casual passers-through. This is felt most obviously in the fabric of the book and is an integral part of the book's textness, its plenitext.

A second example demonstrates this perfectly and illustrates that even the largest of books can be thought of as hand-held technology. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 2, the substantial Bury Bible, produced in the first half of the twelfth century and now divided into three huge volumes, measures 522mm x 360mm. It was a display volume intended among other things to demonstrate the wealth and authority of the Abbey at Bury St Edmunds. But its de luxe quality did not preclude it from being read; its status might only have added to the moment that a reader had with it, for in this book, every verso of every folio bears the physical testimony of use, even if it's difficult to detect. So intense is the turning of the folio that on some versos, the touch of the successive users' hands has left visible proof of their presence through the abrasion of layers of the membrane:

|

| Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 2, folio 20v (from the Parker on the Web site: http://parkerweb.stanford.edu/parker/actions/page.do?forward=home) |

Blankness here, then, is anything but, and what looks like a stain in the digital image is, in fact, the erasure caused by countless page turnings. Thus, while the manuscript itself may be the antithesis of hand-held technology, to turn the folio is, even so, to hold the hands of readers from centuries past.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

Campus ArchiTEXTure

Today, in the midst of a thunderous downpour, we examined Florida State University's Dodd Hall as an example of text:

Built in the late 1920s, this 'gothic collegiate' building now houses Classics, Religion and Philosophy, together with the FSU Heritage Museum. Inscribed over the doorway in Gothic-style letter-forms is an unattributed quotation:

It's clear, then, from these public words that this building belongs--ideologically, architecturally, and contextually--to an institution of learning. But is it (a) Text? We had a long discussion about the building's textness and its dominant features: its cathedral-like appearance, indicating the reverence with which we should approach these buildings (and their being off-bounds to those who don't belong?); its red brick, FSU-style, corporate identity. It is also a building that, like a chapter of a book, belongs to something much larger than itself: one instance of its co-textual (or syntagmatic) relationship with other 'legacy' buildings on campus is its place as #8 on the list of Legacy Walk things-to-see. These are the markers and buildings that remind onlookers and participants of the history of FSU and those who have passed-through its doors (http://www.fsu.edu/~legacy/).

Of most concern in reading this building as Text, though, was its intentionality. If the architect built this building as a library, and wasn't concerned with some larger meaning (no 'intentionality'), then does meaning inhere in it at all? Is it a text if Text = meaning? Well, rather like the adaptive reuse of medieval buildings in modern contexts, its meaning changes, and the onus of textness is on the reader (back to Barthes!), rather than the object itself. The text means something different to each participant; that is, text is necessarily subjective. As such, this building we pass on most days takes on a textual complexity that is performative, eventful, and unstable. We might wonder, then, if all Text, at all times, is ultimately unstable?

Built in the late 1920s, this 'gothic collegiate' building now houses Classics, Religion and Philosophy, together with the FSU Heritage Museum. Inscribed over the doorway in Gothic-style letter-forms is an unattributed quotation:

It's clear, then, from these public words that this building belongs--ideologically, architecturally, and contextually--to an institution of learning. But is it (a) Text? We had a long discussion about the building's textness and its dominant features: its cathedral-like appearance, indicating the reverence with which we should approach these buildings (and their being off-bounds to those who don't belong?); its red brick, FSU-style, corporate identity. It is also a building that, like a chapter of a book, belongs to something much larger than itself: one instance of its co-textual (or syntagmatic) relationship with other 'legacy' buildings on campus is its place as #8 on the list of Legacy Walk things-to-see. These are the markers and buildings that remind onlookers and participants of the history of FSU and those who have passed-through its doors (http://www.fsu.edu/~legacy/).

Of most concern in reading this building as Text, though, was its intentionality. If the architect built this building as a library, and wasn't concerned with some larger meaning (no 'intentionality'), then does meaning inhere in it at all? Is it a text if Text = meaning? Well, rather like the adaptive reuse of medieval buildings in modern contexts, its meaning changes, and the onus of textness is on the reader (back to Barthes!), rather than the object itself. The text means something different to each participant; that is, text is necessarily subjective. As such, this building we pass on most days takes on a textual complexity that is performative, eventful, and unstable. We might wonder, then, if all Text, at all times, is ultimately unstable?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)